Pneumatic Sponge Ball Accelerator

Interactive Installation

Funded by Gemeente Groningen, Kunstraad Groningen and GasTerra

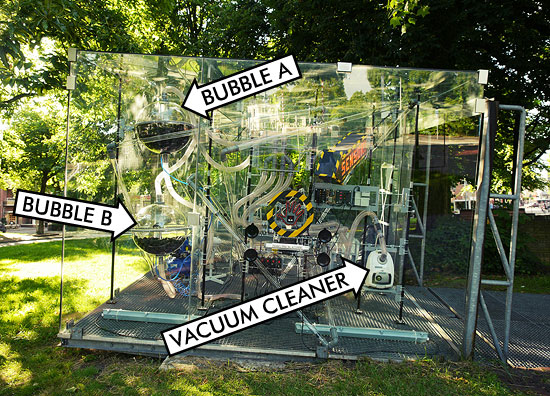

The Pneumatic Sponge Ball Accelerator contains 1000 black sponge balls, which are sucked through 150m of transparent pneumatic tubes with the power of a regular household vacuum cleaner. The balls travel with a speed of about 4m/s. Visitors can operate the machine with a touch sensor mounted on the pavilion’s front glass: They can change the direction of the airflow and watch the balls speed up, slow down and reverse.

Some background for this project

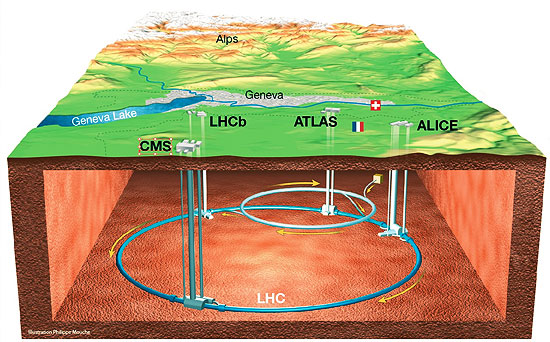

‘Cosmotron’, ‘Bevatron’, ‘Proton Synchrotron Booster’ and also CERN’s well known ‘Large Hadron Collider’ (LHC) – particle accelerators aren’t just gigantic machines (the LHC is 27km in diameter and currently the largest machine on earth) but they also have supercool, cryptic names. While their names are already quite incomprehensible, it’s even a greater mystery what happens inside them: Because there’s basically nothing to see. This is a bit counterintuitive, as the purpose of most particle accelerators is the observation of the behavior and nature of particles. The reason for this invisibility-problem is that the particles which those machines accelerate are unfortunately too tiny to be seen with the bare eye.

Image credit: ©CERN / Philippe Mouche

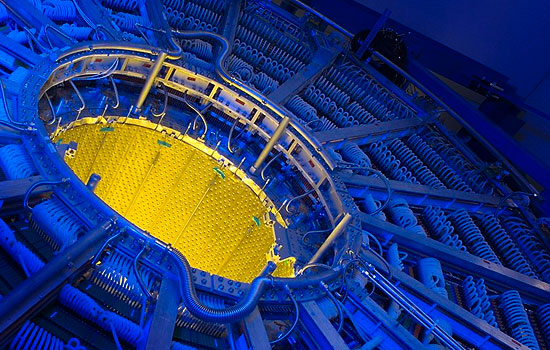

Scientists have recognized this problem and found a clever workaround: They have built other huge machines, just to detect the accelerated particles. Those machines seem to be quite complicated, as they consist out of several subdetectors, which have again very cryptic names. LHC’s ALICE detector, for instance, is comprised out of devices called a ‘Silicon Pixel Detector’, a ‘Photon Spectrometer’, and even a ‘Time Projection Chamber’, which sounds like it comes straight out of the imagination of a science fiction pulp magazine writer.

Photo ©CERN

So let’s face it, most particle accelerators are toys for just a handful of geeks with very special interests, and far away from entering the mass entertainment market. They are too big and too complicated. And although they do a pretty good job in accelerating particles, they fail to provide a joyful observation experience due to the particles’ minute size. There’s just one exception: Electrostatic electron accelerators, also known as cathode ray tubes, did manage to entertain some common folks in the last century. Today, they’re outdated – but that’s a whole different story.

As I’m a fan of science and physics in particular, I find it a pity that the current particle accelerators make the observation of the little speedy particles so complicated. This should be something that a broader audience can enjoy! So when the Director of the Tschumi Foundation approached me and asked me if I’d like to build a machine inside their beautiful pavilion located in the center of a roundabout in Groningen, I saw my chance: I decided to construct a machine which would bring the tremendous joy of particle acceleration to everyone!

How the Pneumatic Sponge Ball Accelerator works

The general workings of this machine are rather simple. The accelerated particles

are black sponge balls with a diameter of 42mm – their size already helps a lot

in perceiving them. The balls reside in two transparent plastic spheres, which I

call ‘Bubble A’ and ‘Bubble B’.

The bubbles are connected to each other via a long airtight track of transparent

acrylic pipes that zigzag through the entire pavilion. The particles move through

those pipes from one bubble to another with the power of an ordinary vacuum cleaner.

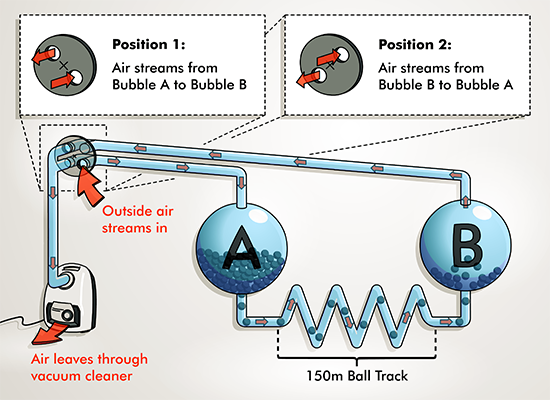

Now let’s get deeper into detail. The movement of the particles from one bubble to another is created by a difference in air pressure. When the vacuum cleaner is sucking air out of Bubble B, it lowers the air pressure inside this bubble, which will be equalized immediately by the incoming air from Bubble A. This creates an airflow between the bubbles, which entrains the particles.

However, if the vacuum cleaner would be left on for a while, all the balls would

eventually accumulate inside Bubble B, while the other one would become empty.

Although certainly fun to watch, this would be a rather short observation

experience.

Therefore the machine contains an elaborate switching mechanism, which allows

changing the direction of the airflow, thus keeping the balls moving between the

bubbles. At least as long as someone operates the machine.

The airflow switching mechanism is just a gear with two holes in it. Pipes are connected to the gear from both sides. And depending on the position of the gear, the holes allow the air to flow through different pipe combinations while other pipes are blocked. It was the most simple design I could come up with and it worked perfectly.

In case you’re a really good observer, you might have also spotted the little

blue compressor in the pavilion, which is connected to the bubbles via a blue hose.

This is not driving the sponge balls in any way. I just thought it would be a good idea

to shoot compressed air into the bubbles from time to time in order to loosen stuck balls

a bit. But it didn’t help much. Surprisingly, the balls love to lock

themselves in geometric

FCC / HCP – structures,

so tight that it becomes almost impossible to empty the bubbles completely.

In case I’ll have the chance to work on a new version of this machine, I’d like to redesign the airflow inside the bubbles in such way, that the incoming air creates a vortex. Hopefully this will be so strong that the balls always spin and never pack densely. That should look cool, too! In the meantime, I’ll watch my Dyson for inspiration.

So much about the airflow. Now about the experience of operating the machine.

The machine is switched on by the people who pass the pavilion. That works quite

easy with a touch sensor installed at the front glass of the pavilion.

Once the Pneumatic Sponge Ball Accelerator is running, the airflow can be reversed by

touching the sensor again. Visually, it is a very impressive experience to see all

the balls race through the pipes in very high speed. They are so fast, it is almost

impossible to follow them. But when you reverse the direction of the airflow,

hundreds of balls slow down all at the same time, just to speed up in the other

way one moment later.

Even though there exist some off-the-shelf solutions for touch sensors, I preferred

a DIY construction for two reasons:

I had to have a sensor which works very reliably and I had no chance to test it at the

spot beforehand. The glass of the pavilion is so thick, that I didn’t want to go

for a capacitive touch sensor. As it had to work in bright sunlight, using an infrared

distance sensor wasn’t a good idea, either.

At the end, I’ve built a simple optical sensor which consists of a couple of rapidly blinking LED’s and a photo resistor. The LED’s are positioned in a such way, that their light doesn’t hit the photo resistor unless a hand reflects them onto the photo resistor. It turned out to work really well, during day and night, and also when the glass was covered by raindrops!

I also wanted the sensor to look very appealing to touch. So I decorated it extravagantly

in the shape of a hand. A cheesy deco lamp provided 500 thin optic fibers, which I’ve

arranged carefully to shape the outline of a hand. The optic fibers are lit by a

very strong RGB-LED spotlight,

which switches from red to green if someone touches the sensor. In order to add a

cool 80s disco effect to the light, I mounted a slowly spinning acrylic glass disc

between the spotlight and the optic fibers. The disc has some drips of epoxy and

opaque adhesive tape on it, which cause the light to change its intensity in a

very organic way. The end result is quite magical and looks almost like lava.

I completed the sensor by adding illuminated instructions written on a plastic tube and

a gigantic rotating arrow pointing on it. The words “ACTIVATE”

and “SENSOR!” on the arrow leave no doubt that this

contraption is supposed to be an interactive installation!

You can see the optic fibers, the rotating acrylic disc, the LED spotlight and some random electronic parts

Conclusion

Despite minor flaws, the general concept worked exceptionally well!

People loved the machine. The visual experience of observing the

hundreds of balls accelerating in the pavilion seriously kicked ass.

One of the first random visitors (a neighbor of the Pavilion) turned out to be a

theoretical physicist who even used to work at CERN on

the LHC. With him I had an insightful discussion about

particle accelerators. He told me that the particles inside the LHC

move in both directions as well, at the same time, just separated by magnetic fields, until they crash in a detector.

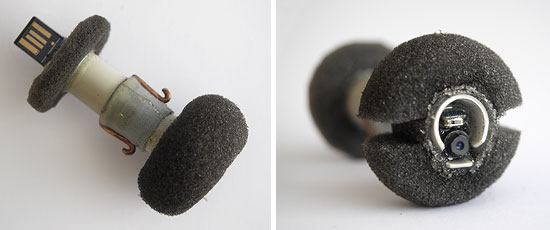

Nevertheless, I was interested in even more insight! I wanted to see how the ride looks

like from ball perspective. So I have bought a little spy camera and modified in such

way that I could suck it through the pipes.

Of course, I have also uploaded the video which came out of this experiment. It is a bit shaky and wobbly and very fast. The camera has a strong rolling shutter effect, which results in quite psychedelic image distortions. Well, see for yourself. I haven’t edited the footage because I think it makes quite interesting source material for club visuals (or so). Please feel free to reuse and remix it!

Special thanks

I want to thank Wouter Reckman, who was my setup helper and who cared for the installation during the whole exhibition period. Since he was a skilled programmer, he also took over the code and added data-logging and remote control functionality to it!